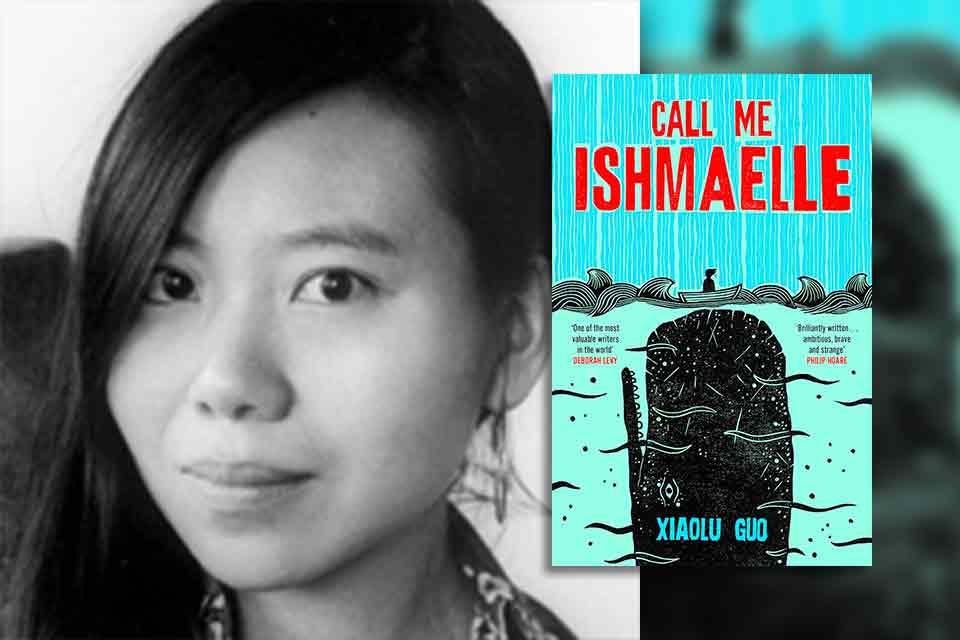

The title of Xiaolu Guo’s new novel, Call Me Ishmaelle (Chatto & Windus, 2025), instantly reminds us of the famous opening of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, “Call me Ishmael.” At the same time, the change in gender, from Ishmael to Ishmaelle, catches our eye. Apparently, the mysterious narrator in Melville’s novel is now reborn as female. On an all-male whaling ship, the unexpected presence of a young, female, English sailor foreshadows the many surprises that Xiaolu Guo prepares for us on this journey to sail across the oceans in pursuit of the white whale.

As Guo candidly acknowledges, Call Me Ishmaelle is an homage to Moby-Dick (1851). Although, apart from Ishmael, the male pseudonym the heroine later adopts, the names of all the other characters have changed, the plot and characterization of the novel keenly resemble that of Moby-Dick. There is Captain Seneca, who lost one leg to the white whale and whose entire existence is aimed at killing the latter. There is Kauri, a Polynesian harpooner who closely resembles Queequeg. Both are covered with tattoos and have shared the same bed in a small inn with the narrator before they boarded the whaler. At the end of the novel, the captain and all crew members lose their lives in the fatal battle against the white whale, with Ishmaelle being the only survivor.

One might wonder, What is the point of rewriting a canonical American novel in the twenty-first century, particularly if the plot and characters remain largely similar?

In an interview with The Guardian, Guo talked about the reason she wrote this novel. She was in New York and wandered about as a foreigner. As with every novel she wrote, she asked herself in what ways a non-Westerner from a nonbiblical background could engage in dialogue with the Western literary canon. We all know that Melville infused Moby-Dick with a profound Christian ethos. It was then that Guo wondered, “What if people never knew what that [Christendom] is? If it said ‘Taoism’ instead, would you still listen to the story?” This is the key to opening the treasure box that is Call Me Ishmaelle. Rather than a simple imitation or adaptation of Moby-Dick, it is an experiment to engage with canonical Western literature on the level of both form and theme. The novel that Melville wrote over a hundred and seventy years ago is reborn in multiple dimensions.

The rewriting of canonical works—this includes adaptation, anthologizing, translation, and new editions—represents, in fact, the afterlives of those works.

Literature ages. However much we literary scholars resent this statement, there is some truth in it. Younger generations nowadays read all those jazzy-colored books about training dragons and transforming into demigods, instead of Beowulf. The rewriting of canonical works—this includes adaptation, anthologizing, translation, and new editions—represents, in fact, the afterlives of those works. They allow these masterpieces to reach later generations of readers who may come from different cultural backgrounds or have a different upbringing and education. Call Me Ishmaelle, by engaging with Moby-Dick, endows the latter with an afterlife and draws readerly and academic attention once more—if through the refraction of the latter novel—to the canonical work.

More significantly, the very creativity of literature comes from intertextually engaging with earlier works. We used to believe in the “talent” of individual authors, thinking they have things to say that no one else has ever said. But that has proved impossible, as Julia Kristeva and Roland Barthes long ago pointed out. If we look at all the masterpieces of world literature, we see how later writers borrow and adapt from earlier ones. Just as T. S. Eliot remarks so incisively,

One of the surest tests [of the superiority or inferiority of a poet] is the way in which a poet borrows. Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different than that from which it is torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest. (The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism)

Indeed, I can’t agree more with Eliot that good poets borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest. Many brilliant contemporary literary works were written by creatively engaging with earlier works. One of my favorite writers, Kazuo Ishiguro, wrote The Buried Giant by masterfully engaging with the fourteenth-century chivalric romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Unlike Sir Gawain, who fought the dragon as a young man in the original romance, the Gawain in Ishiguro’s story is an old man who pretended to fight the she-dragon but was actually determined to protect her. As a writer of Japanese heritage who immigrated to the United Kingdom at the age of five, Ishiguro forms an interesting comparison with Xiaolu Guo in many ways. Both have East Asian heritage, write in English, and live in the UK. While Ishiguro creatively borrowed from a work of English verse, Guo engages mainly with an American novel, although, apparently, she also engages with Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Shakespeare, among others. What is interesting is that people have long recognized the “Englishness” of Ishiguro’s works, yet we would not say the same of Guo’s. Rather than “Englishness” or “Americanness,” her works have always disrupted the canon and subverted the English language itself.

Rather than “Englishness” or “Americanness,” her works have always disrupted the canon and subverted the English language itself.

In her first novel written in English, A Concise Chinese–English Dictionary for Lovers, published in 2007 and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, Guo already demonstrated her boldness at linguistic experimentation and the ingenious way she tied language with the work’s theme. In the story, the heroine, who arrives in London for the first time, speaks broken English and is constantly shocked by the new culture she finds herself in. As she adapts to the new culture and experiences a romantic relationship with an English man, her English level improves, and she matures as a young woman.

A similar experiment was carried out in Xiaolu Guo’s later novel, A Lover’s Discourse, published in 2020. The repeated use of the dictionary form reveals Guo’s fascination with linguistic experiments, whereas the prominent presence of the Chinese language has shaped what readers and critics see as an essential feature of Guo’s English-language works.

Hence the surprise when Call Me Ishmaelle came out. The Chinese language no longer forms an integral part of the novel’s structure. Rather, we see large paragraphs that describe the internal monologue of Captain Seneca, who, contrary to Captain Ahab, is Black. An educated Black man whose father is said to have been killed by a white mob—and who was raised by a Quaker family—Captain Seneca considers him neither a good Quaker nor a good Black man. As the story unfolds, we get to understand his real reason for chasing the white whale: his wife betrays him and elopes with a white man while Seneca is at sea. As the third mate Jacque points out, “He should have killed that white man! Instead, he turns on the white whale!” The monologues of Captain Seneca are written in first person, terse, stoic, with no punctuation marks at all. Such a unique linguistic style forces readers to concentrate on Seneca’s monologues, and readers find themselves immersed in Seneca’s painful past, his powerful emotions, and his lived experience.

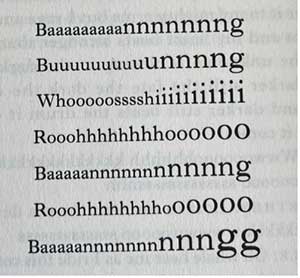

What pushes the boundary of language even further is Guo’s representation of the whale’s language. There are quite a few episodes in the novel that consist, sometimes solely, of the whale’s singing.

By giving voice to the whale and juxtaposing the whale’s monologues with those of Captain Seneca, Guo makes a radical move toward ecocriticism.

The way Guo represents the whale’s sounds resembles experimental poetry, where poets use the size of letters and the repetition, positioning, and arrangement of words on the page to express meaning. By giving voice to the whale and juxtaposing the whale’s monologues with those of Captain Seneca, Guo makes a radical move toward ecocriticism. Although ecocriticism was already a prominent theme in Moby-Dick, Guo pushes this intervention further by using linguistic experiments to show, rather than tell, readers that the nonhuman world also has its subjectivity. Whales, like Captain Seneca, suffer violence and cruelty.

We are therefore delightfully surprised by Guo and, once again, see her breaking the confines of her former success with linguistic experiments. Instead of playing with the fraught relationship between such languages as Chinese and the dominance of global English, she gives shape to the delirious monologues of a half-deranged captain and the agonized cries of wounded whales. These formal experiments point us to the themes of her new work.

On that point, we come across the presence of Chinese culture. Just as Guo promises in the Guardian interview, she does bring Taoism into this novel. On the first page there is a quotation from Tao Te Ching, the most famous Taoist work:

Heaven and earth are indifferent;

They view all creatures as straw dogs.

The sage is likewise indifferent;

He too views common people as straw dogs.

Between heaven and earth, the space is like a great windy chamber:

empty yet inexhaustible.

Its turbulent air brings forth unceasing energy.

This seemingly insignificant quotation plays a key role in the novel, as it represents the Chinese—particularly the Taoist—worldview. The quoted verse embodies the Taoist philosophy of “letting the world be and the universe can govern itself.” In other words, humans should not see themselves as masters of the world and should not overestimate their ability to transform nature. In fact, this is also an idea that many believe Melville wants to convey in Moby-Dick. The difference is that, while Melville criticizes man’s arrogance and ambition, Guo stresses the importance of respecting nature and limiting human intervention in nature. Such an idea is encapsulated by the mysterious character of Muzi, a character Guo adds to the story. Muzi is a sailmaker and Taoist, an old acquaintance of Captain Seneca, and the only man on the whaler who exerts a strange influence on the eccentric captain. He uses wooden sticks to tell fortunes, based on another Taoist classic, I Ching (The Book of Changes). The only time Seneca refuses to listen to Muzi’s consul is when all, except Ishmaelle, lose their lives in the final battle against the white whale.

While Guo fulfilled her promise of bringing a non-Western worldview into her new work, one can’t help but wonder about the characterization of Muzi. A small man with “a special kind of aura around him,” with black hair neatly tied into a bun on top of his head, Muzi appears to be odd and out of place on the whaling ship. Such characterization seems to have somehow fallen into the Orientalist stereotype against which Guo’s earlier works fought hard. It is understandable that there are limited options for characters who live on a whaling ship, yet we do wish to see more rounded characters from East Asia who have emotional and intellectual depth, just like Ishmaelle herself.

In any case, Xiaolu Guo’s new work needs to be read against the many layers of Moby-Dick, which she engaged with either by subverting them or by pushing them further. Its bold linguistic experiment pushes Guo’s own creative boundaries and is delightfully surprising. She has offered us new inspirations on how writers from non-Western backgrounds can connect with canonical works of world literature. Needless to say, the novel itself is a pleasure to read, full of excitement, humor, and thrill, allowing readers to embark on a quest for personal growth, freedom, and reconciliation.

University of Warwick

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·