Nothing arrests me quite like a description of a very hungry woman. When I see a woman let loose with fistfuls of chocolate mousse or cherry danishes or apple streusel, I know that big things are in store. We learn early that we will be punished for being too hungry or wanting too much; to give into those appetites can lead to growth or destruction. Sometimes both at the same time.

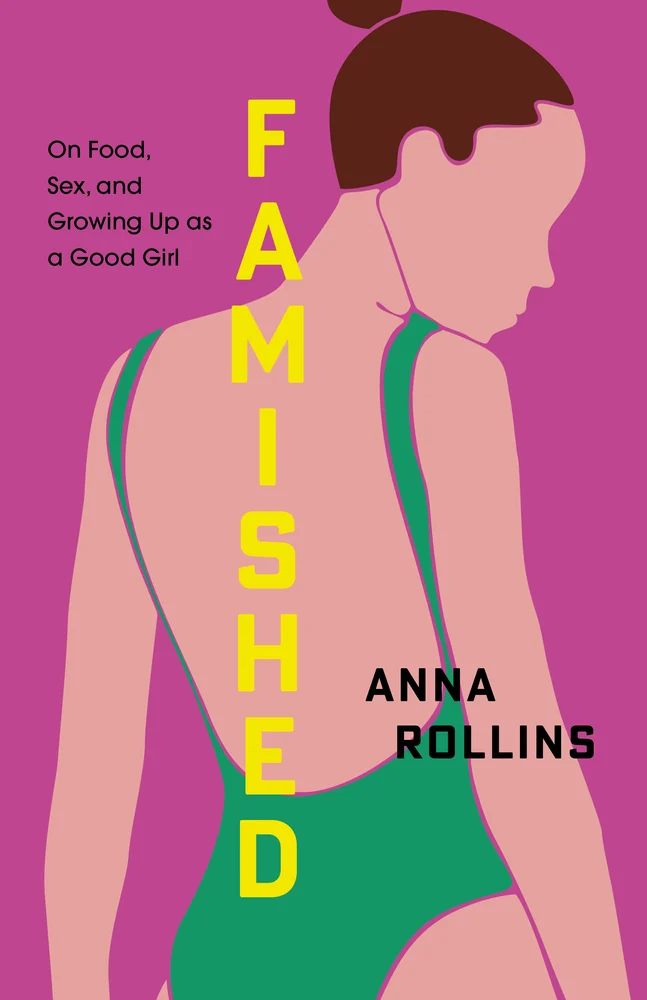

I open my reported memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl, with a description of my child self in the kitchen, foraging and devouring all the things in the cabinet as if in a fugue state: granola bars, cereal, muffin tops scattered all over the floor and torn to bits—as if an animal had been let loose. Though I had swallowed the belief that smallness and restraint would keep me safe, pure, and holy—beliefs fed to me through the rhyming scripts of evangelical purity culture and diet culture—my body resisted these restrictions. Bingeing on food filled me with shame, but it was also a vital signal that I was hungry for more, that I was longing for life.

In the books below, women are hungry for love, survival, and power. They often find themselves in situations where their desires are under threat. In this tension of unfulfilled want, they act out the extent of their appetites at the table. For each of these women, food indulgence runs parallel to their other, gnawing appetites. They may not get precisely what they long for, but they will not walk away from these narratives empty. Their hungers will not eat them alive.

Vladimir by Julia May Jonas

In this campus novel, a faculty couple destructs after the husband comes under investigation for inappropriate relationships with former students. The wife in the duo copes with the rift in her marriage and professional life by pursuing a junior colleague. Before this pursuit, though, she gives into desire at the dinner table, making and gorging upon an elaborate meal of expensive parmesan, anchovies, dark black kale, salami, olives, raspberries, sourdough, martinis, and a flourless ganache chocolate torte. This visceral description of unbridled consumption precedes her own obsessive desire.

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

In this novel, true love means abandoning one’s religion of calorie restriction for the indulgences of the flesh: or, ice cream sundaes. When Rachel meets Miriam at the ice cream parlor, she falls in love with her otherness: Miriam’s openness to life and food, her expansive body, and her self possession. As the two become one, Miriam’s free relationship with desire leads to Rachel’s own conversion.

Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist

Lundquist’s tender memoir unpacks the trope of “the beard”: a heterosexual woman who unknowingly enters into a relationship with a closeted gay man. Raised in conservative evangelical culture, she and her partner digested rigid narratives about gender roles. To live up to the expectation of being a desirable, traditional woman, many of Lundquist’s scenes include descriptions of hunger and obsessions with weight loss. But mid-narrative, there’s a shift: She begins to indulge. And grow. In one evocative scene, after being told she was “getting too damn skinny,” she shovels fresh pesto straight from the blades of a blender into her mouth, the licorice and pepper taste of basil intermingling with traces of blood from her tongue.

The Wall by Marlen Haushofer

How much hunger does it take to survive at the end of the world? In this feminist novel, the unnamed main character discovers her own agency and self-sufficiency as she forages for berries and hunts game. In a world no longer populated with people (or so it appears), she creates community with animals—most notably her cow, Bella. Bella’s milk—and all the butter and cheese that can be made from it—becomes the narrator’s most sensuous indulgence, a small remembrance of the ways kinship and community are central to our enjoyment of meals.

I Used To Be Charming by Eve Babitz

Consider Eve Babitz in contrast to her mentor and long-rival Joan Didion. On the page, Didion offers minimalist restraint. But Babitz? Her lines are filled with indulgence. In this collection of essays published in popular magazines, Babitz celebrates all forms of desire. And in the title essay where she describes a life-altering accident that resulted in third-degree burns over half of her body, her recovery is described in tandem with her craving for tuna sandwiches.

The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood

Nicole Graev Lipson Turns to Literature to Rewrite the Societal Roles Expected of Women

Her memoir in essays “Mothers and Other Fictional Characters” challenges the harmful stories forced upon women

Women’s bodies shrink as their rights shrink. Diets have long been considered through a feminist lens: If a woman is hungry and turned inward, she doesn’t have the energy or perspective to change the outside world. But in Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman, this reading of restriction is upended and considered in terms of awakening rather than submission. As Marian approaches an uninspiring marriage, she rejects food as a form of protest. At the conclusion, she bakes a cake shaped like a woman and insists that her fiance become the consumer. Disgusted, he refuses and leaves her. She eats some of her own cake, and with this act, her appetite returns.

All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess by Becca Rothfeld

Excess, gluttony, maximalism, and, quite frankly, just being a little too much? Becca Rothfeld celebrates it all. In this collection of essays, she contends that “all things are too small” because it is a torment to realize all that we will never be: “we are not a plate of pasta or a whale or every word in the English language or, most painfully, each other.” Our hunger is a vital sign of our longing for life and our desire to experience a world outside of our own singularity.

The post 7 Books About Very Hungry Women appeared first on Electric Literature.

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·

Bengali (Bangladesh) ·  English (United States) ·

English (United States) ·